Lost, but making good time

Switching to sales as a non sales-person

I’m re-reading the fantastic Competing against Luck at the moment. One of the opening quotes from the book is by the famous baseball star Yogi Berra – ‘We’re still lost, but we’re making very good time!’

Clayton Christiansen was referencing the feeling of progress that feels good but ultimately doesn’t end anywhere. He was talking about innovation in large business primarily, but boy did it hit me right between the eyes.

As two technical founders (it’s taken me a while to be comfortable calling myself technical but I’ve written a lot of code in the last 6 months) it’s really easy to fall into this fallacy. Our github profiles are gleaming – we’re shipping a bunch of code. Quiet focus, few meetings, complete alignment. We can get a lot of shit done.

But we looked up last week and realised that while we’ve been having plenty of customer conversations to improve the product, we hadn’t been deliberate about how we were spending our time. We weren’t caring enough about sales.

How did we get here?

I’ve seen a bunch of debate about solo vs co-founders recently, and many people saying that ‘you shouldn’t see finding a co-founder as necessary’. There’s even been this flawed study floated around, with the headline “Solo founders are twice as likely to succeed in business as co-founders”.

I get why. Silicon valley and the startup ecosystem common parlance is that you need a co-founder. In fact accelerators like YC effectively demand it by saying they rarely accept founding teams of one. However many – especially indie – makers, just want to crank on their business without the overhead of another person. And of course there are some good examples of solo founders working out (though ask previous co-founders of Zuck how he got there and many of us may be uncomfortable with the cost).

I personally have worked for two solo founders. Not a good sample size to determine whether it helped with focus or business success, but interesting to watch how the dynamics played out. One had a co-founder for a while who didn’t work out, the other tried very hard to find one but couldn’t. One made their company a huge success, the other didn’t.

What I definitely saw though, was the mental strain it took to run a company, with a board, staff, customers and expectations, on their own. I knew I wanted a co-founder if I was to ever start something myself.

What’s incredible though from day one, is that there are two of you. That means you can divide and conquer. But we weren’t doing that, and it was largely my fault.

Giving away your toys

Bringing Neil on after working on the business for a while has meant that he’s had to ramp up – both in terms of the ‘institutional knowledge’ in my head, but also in terms of passion for the problem. It hasn’t helped that I’m not fantastic at giving things away. As a result, even though Neil’s strength is in the code, I’ve been building stuff myself. It’s deeply fun, but I don’t need to be doing it.

In the code everything is cosy. You write something, it works, you ship it, it’s out there. It doesn’t reject you, it doesn’t ghost your meeting or not reply to your emails. It won’t gradually inform you that what you’ve built isn’t useful, or that you’re pricing it wrong, or explaining it badly. It loves you unconditionally.

A new respect for sales people

People are much harder. They have problems that you can’t put your finger on, they have budgets you can’t read and bosses that you can’t speak to. They’re rightly busy doing their jobs, so getting to the truth may just take more time than they have to give. They may also be lying to you.

It creates a process that has far less of a correlation to time spent, and the dopamine hits are far less predictable and far less frequent.

We’re sitting on a bunch of potential customers across waitlists and conversations. And I’ve been scared to do anything with that list. Because what if they reject me? What if what I’ve spent over a year working on is all for nothing? What if I’m making a fool of myself?

Focus

So Neil and I mapped our time. Very quickly I realised there were a few glaring things that I was doing – or not doing – that were jeapordising the business.

- I jump into code without consciously working out whether it has to be me that does so.

- I’m not clear enough on how much I expect to be involved in ‘building the thing’

- I spend a lot of time spinning wheels on what the right thing to build next is, but am not using the most valuable resource I have – these people who have self-declared as having ‘some sort of a problem to solve’ – to guide me

- I spend waaaay too much time writing code.

As a designer I’m used to being part of the problem definition and solution process. And of course, in a product company, that should be our bread and butter.

But I’ve also come to the realisation that – especially as we’re creating a new spending category for our customers to contend with – I need to be selling. The sales process won’t just accelerate our revenue (which we definitely need to do) but will accelerate our learning too.

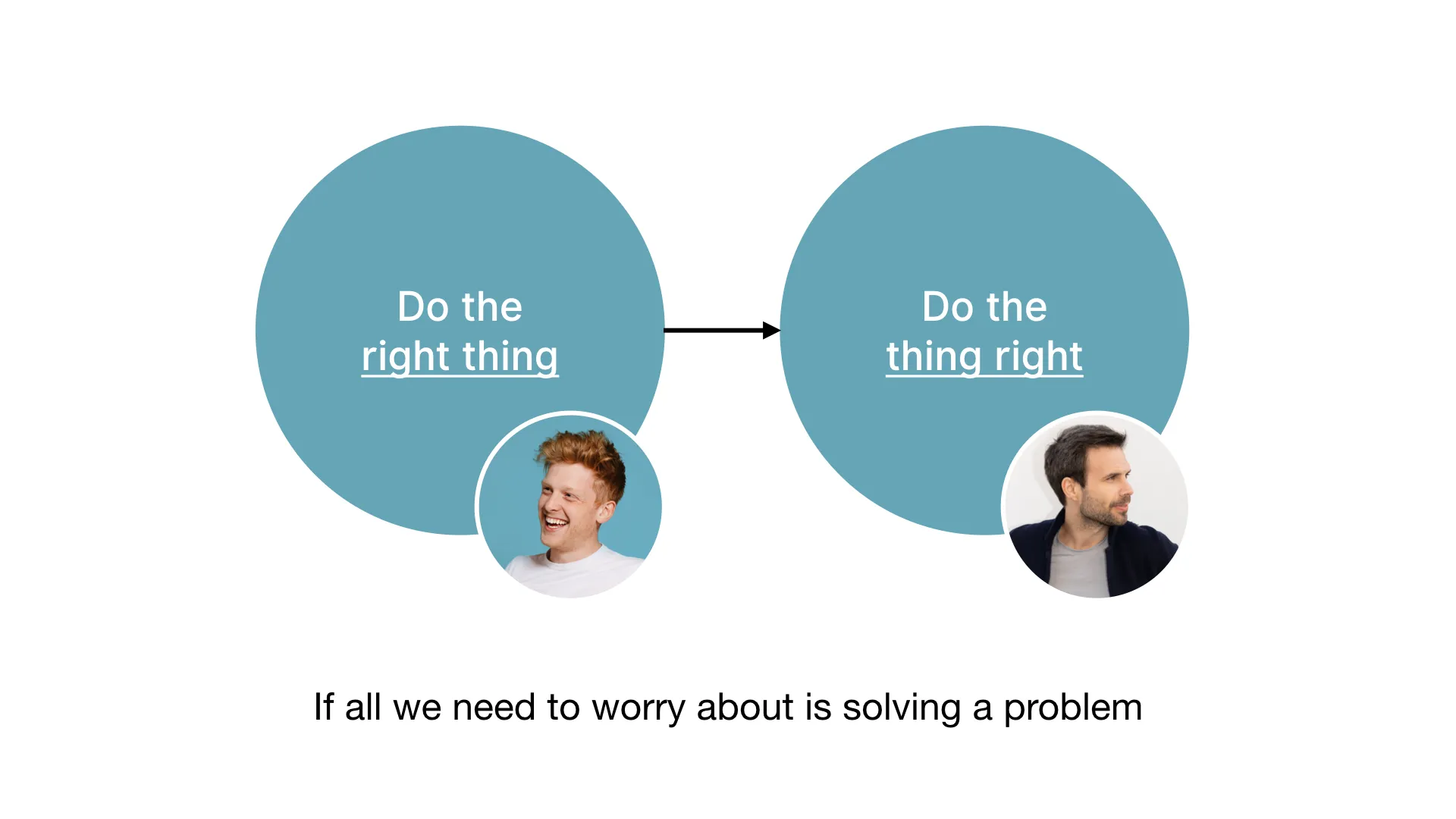

Only worrying about solving a problem

We’ve been locked in this mode – running fast but not having a good enough sense of where we’re running to. But what we need to get to is walking steadily in a direction we understand.

Only worrying about solving a problem

We’ve been locked in this mode – running fast but not having a good enough sense of where we’re running to. But what we need to get to is walking steadily in a direction we understand.

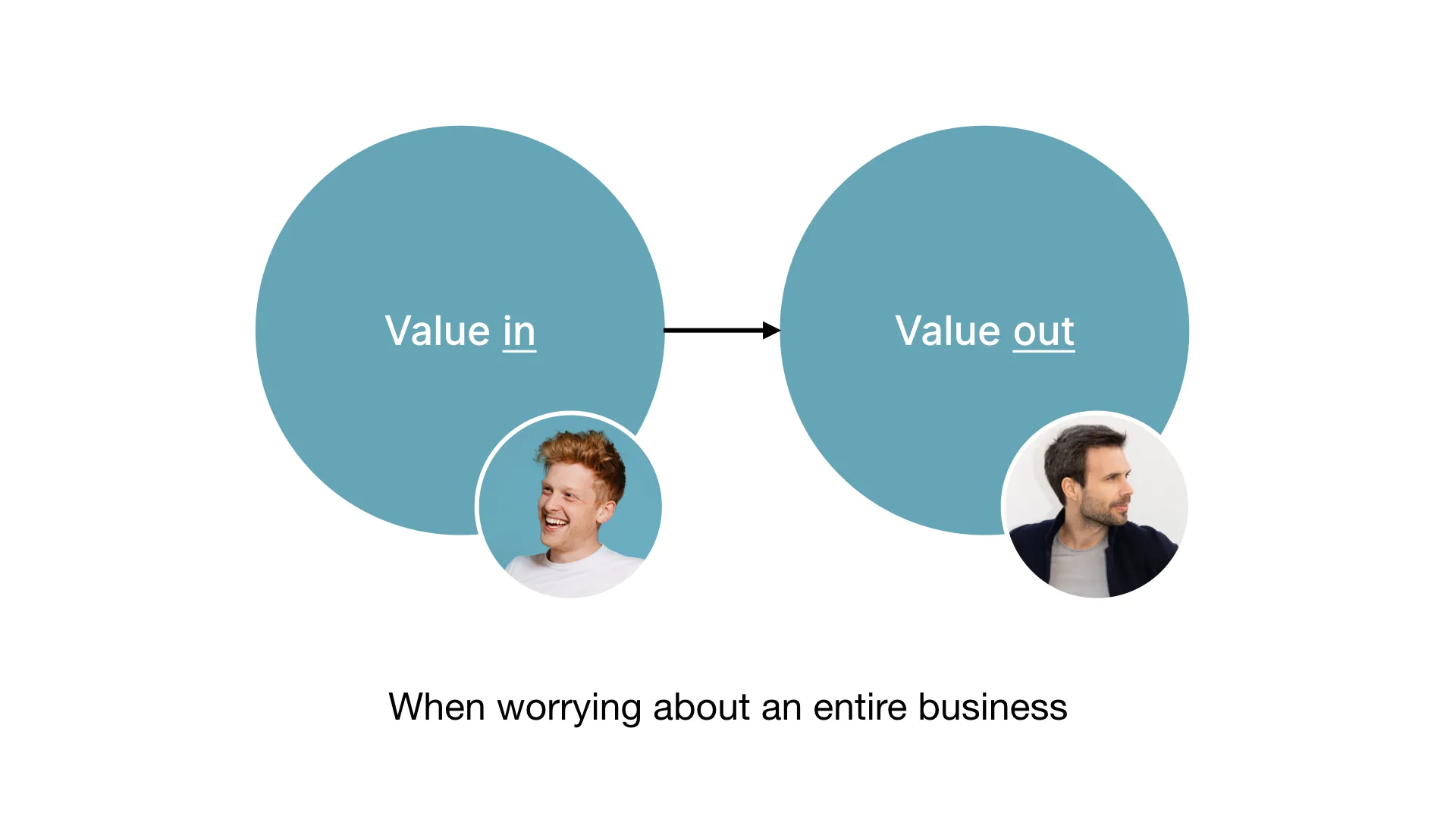

Thinking about creating a viable business

Thinking about creating a viable business

I need to be putting all my time into the first part, and letting Neil own the second.

So we’ve put together some simple heuristics to get me weaned off committing code. Some are obvious, others less so.

1. I’m only allowed to be involved in product for 1 hour a day

Sounds hardcore right? But think about it: in an hour I should be able to (a) write tickets or comment on any upcoming work, (b) review any open pull requests that need my attention and (c) do any functional testing on work that’s shipped to our staging environment, or production. And just that forcing function will keep me in check when I feel like hacking on something unimportant because it’s fun.

Notable by its absence is spending time actually designing. But honestly, we now have a UI toolkit that can get us 80% of the way there, and Neil has a good eye. So I’m spending very little time in Figma anyway. It’s fairly common that we co-design with a marker on A3, and the result is pretty much there.

2. I’m primarily reporting on learning and conversations in our standups

No more ‘I’ve thought of a new thing we could build’, or ‘what if we did this’. What did I move across my ‘value in’ kanban? The time for noodling is over.

3. Neil is fully responsible for the quality of the product that ships

One thing that we possibly haven’t been as conscious over is explicitly ensuring ownership is shared. From now on, bugs or low quality implementation is primarily Neils problem. That practically means I can’t just do late night pushes to production, and we’re writing tests. Hooray!

4. There’s an expectation that when code is handed to me, it’s as good as it can be

This is slightly more nuanced, but we’ve so far been focused on speed to ship. Switching our focus more to quality means that code is reviewed later in the process, and it’s really for spotting UX issues and resolving subjective decisions rather than finding obvious holes. It may well slow us down, but should (a) save me some time and (b) improve our quality.

Anyway, we’ll see how it goes with me full time on sales. I’m seeking the advice of experience sales folks, so if you know someone with early stage SaaS sales knowledge please do let me know!